It was a goat herder named Kaldi, so the story goes, who first noticed the effect of coffee beans on the the energy levels of his goats. After telling the local abbot of his observations, the monks at the nearby monastery realised that this drink could help them stay awake during prayer and so the reputation, and consumption, of coffee spread from Ethiopia and then throughout the world.

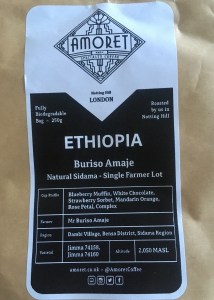

While the details may be questionable, there is evidence that the coffee plant originated in Ethiopia. Coffee still grows wild in parts of Ethiopia and the oldest varietals are also to be found there. And so, when I realised that my latest coffee was an Ethiopian Natural of varietal Jimma 74158 and 74160, roasted by Amoret coffee in Notting Hill, I thought, why not do a coffee-physics review rather than a cafe-physics review? For there are always surprising links to physics when you stop to think about them, whether you are in a cafe or sampling a new bag of beans.

This particular coffee was grown by Buriso Amaje in the Bensa District of the Sidama region of Ethiopia. The varietals were selections from the Jimma Research Centre from wild plants that showed resistance to coffee berry disease and were also high yielding. Grown at an altitude of 2050m, the naturally processed coffee came with tasting notes of “Blueberry muffin, white chocolate” and “rose petal” among others. Brewed through a V60, it is immediately clear it is a naturally processed coffee, the complex aroma of a rich natural released with the bloom. Indeed, the bloom was fantastically lively with the grounds rising up with the gas escaping beneath them in a manner reminiscent of bubbling porridge (but much more aromatic). And while I lack the evocative vocabulary of Amoret’s tasting notes, the fruity and sweet notes were obvious, with blueberry a clear descriptive term while I would also go for jasmine and a slight molasses taste. A lovely coffee.

Brewing it again with an Aeropress, the tasting notes were different. We could start to ponder how the brew method affects the flavour profile. But then we could go further, how would this coffee taste if brewed using the Ethiopian coffee ceremony? Which leads to further questions about altogether different origins. Where did this come from and how do our methods of experiencing something emphasise some aspects while reducing others? Ethiopia offers a rich thought current if we consider how things originated because it is not just known for its coffee, Ethiopia is also home to some of the world’s oldest gold mines. Today, one of the larger gold mines in Ethiopia lies just to the North West of where this coffee came from, while a similar distance to the south east is a region rich in tantalum and niobium. We need tantalum for the capacitors used in our electronic devices. In fact, there is most likely tantalum in the device you are using to read this. While niobium is used to strengthen steel and other materials as well as in the superconductors within MRI machines. Where do these materials come from?

Within the coffee industry there has been a lot of work done to demonstrate the traceability of the coffee we drink. But we know much less about the elements that form the components of many of the electronic devices that we use every day. And while this leads us into many ethical issues (for example here, here and here), it can also prompt us to consider the question even more fundamentally: where does gold come from? Indeed, where do the elements such as carbon and oxygen that make coffee, ultimately, come from?

The lighter elements, (hydrogen, helium, lithium and some beryllium) are thought to have been made during the Big Bang at the start of our Universe. While elements up to iron, including the carbon that would be found in coffee, have been formed during nuclear fusion reactions within stars (with the more massive stars generating the heavier elements). Elements heavier than iron though cannot be generated through the nuclear fusion reactions within stars and so will have been formed during some form of catastrophic event such as a stellar explosion, a supernova. But there has recently been some discussion about exactly how the elements heavier than iron formed, elements such as the gold, tantalum and niobium mined in Ethiopia.

One theory is that these elements formed in the energies generated when two neutron stars (a type of super-dense and massive star) collide. So when the LIGO detector, detected gravitational waves that were the signature of a neutron star collision, many telescopes were immediately turned to the region of space from which the collision had been detected. What elements were being generated in the aftermath of the collision? Developing a model for the way that the elements formed in such collisions, a group of astronomers concluded that, neutron star collisions could account for practically all of these heavier elements in certain regions of space. But then, a second group of astronomers calculated how long it would take for neutron stars to collide which led to a problem: massive neutron stars take ages to form and don’t collide very often, could they really have happened often enough that we have the elements we see around us now? There is a third possibility, could it be that some of these elements have been formed in a type of supernova explosion that has been postulated but never yet observed? The discussion goes on.

The upshot of this is that while we have an idea about the origin of the elements in that they are the result of the violent death of stars, we are a bit unclear about the exact details. Similarly to the story of Kaldi the goat herder and the origins of coffee, we have a good idea but have to fill in the bits that are missing (a slightly bigger problem for the coffee legend). None of this should stop us enjoying our brew though. What could be better than to sip and savour the coffee slowly while pondering the meaning, or origin, of life, the universe and everything? That is surely something that people have done throughout the ages, irrespective of the brew method that we use.

As cafes remain closed, this represents the beginning of a series of coffee-physics reviews. If you find a coffee with a particular physics connection, or are intrigued about what a connection could be, please do share it, either here in the comments section, on Twitter or on Facebook.